This is a proposal for a new method of urban development.

I will attempt to correct a

broad issue that manifests in all societies, and all populations. However as this is in reference to human's impact on nature, the higher the population, the greater

the problem becomes.

In all parts of the

world very basic limiting factors had for most of human history kept populations relatively small and sustainable by the local environment. These limiting factors (such as competition for food and limited habitability in a single area) drove populations apart and provided an influencing element to the spread of humans globally.

Before any common method of land transportation other than by foot or animal was available,

humans occupied most major land masses on Earth.

As spread out as humans were, their impact on the

environment was negligible for most of history. Not that the ancient people of

this world didn't find curious and entertaining ways of destroying the

environment, but due to their localized and limited numbers, this destruction was usually absorbed by nature and healed over time. As populations have grown and technology has progressed, the acts of humans

have become more broad and permanent. A man alone with an axe and a forest to

fell will not likely succeed, or even make the attempt. However a man with an

axe, a cart, and a road to a city with a market for wood, might take down that forest, and get well

rewarded for the effort.

There is a beautiful symbiotic relationship between human labor and city development. It would take a large population to support someone who could specialize in a particular field. For example a man who exclusively but proficiently made shoes would not likely do well alone in a cabin in the woods. Simultaneously a large and closely bound population couldn't exist if people didn't specialize. If every citizen were their own farmer/hunter/fisher/craftsman/carpenter, etc. then not only would there be no need to be close together, it would be a hindrance. Each man having to walk past the next man’s farm to get to the deer. Each fisher having to move out further than the last to get the fish. Everyone constantly on the move to the same places all doing the same things.

The thing that has tied humanity together is roads. Even when

people still had to build walls around their towns and villages to protect from

predators (both human and animal), roads ventured out across the planet. Roads made it so

one village could act as two, two as ten. Villages combined would behave like

cities. Greater and greater specialization was possible. The town by the bay

could provide the best fish, the town by the mountains might have the best

game. With a road in between, each could benefit from the other, and thus began the

vital and amazing network of trade and expansion that defines virtually all

human habitation globally.

When cities were small, and roads of stone or dirt were traveled by foot or by horse, nature, although almost entirely unwelcome in human areas, did fine out on its own. As cities have grown bigger, cities upon cities into metropolitan areas that can span entire mountain ranges or valleys, entirely surround bays or islands, design methodology didn't change very much. In many ways cities and roads became increasingly hostile to wildlife.

For example when an

animal requires a route to migrate, and there is a town or village in the way,

the species could presumably go around and continue with its life. When

cities completely occupy natural areas, entire flood plains, entire

valleys, etc. the animals often no longer have viable alternatives. While the

impact of human expansion in antiquity isn't nearly so well documented, I’m

sure there were comparable stories to the impact humans made when the Europeans

immigrated to the Americas. Europe and Asia each had their own periods where

entire forests were felled, lakes drained, rivers diverted, etc. But since much

of this occurred in recent times in America, there are many examples to pull

from. The complete elimination of old growth forests in the southern states saw

the end of numerous species of birds. Carrier pigeons, once so numerous their

flocks could darken the sky, were entirely wiped off the face of the Earth by

Americans in only a couple generations.

But much of these old mass devastations have been addressed.

We don’t act so cavalier anymore. We have

developed concepts of commercial viability that prevent people from completely

killing off or destroying entire areas or entire species. But something was

missed. Even as environmentalism has convinced people to stop polluting, to try

to create renewable sources and not entirely eliminate them as they progress,

nothing has been done about urban design.

Cities still follow

the same basic principles from over 1,000 years ago. Only now they are more

deadly to animals. Imagine a deer walking across a busy highway. That’s a dead

deer. Maybe not the best example. There are a lot of deer. How about a mountain

lion? Or a bison? Still dead. Probably causing major damage to whoever hits the

animal, and possibly even causing a deadly crash for people too. I've noticed a

pattern whenever I read about rescued animals or wildlife in general, people

constantly bring up hunters. Hunters, the scourge of the earth. Vilified well

in films such as Bambi where the act of killing a pheasant is portrayed as

nightmarishly terrifying and horrific, only to be topped by the killing of

Bambi’s mother. But in reality there are very few hunters in this nation and

none of them are going out to cause terror. If you've ever biked down a busy

road that cuts through mostly wildlife, you will know it is the true great

killer. Roadsides are graveyards.

Before cars were

everywhere at all times doing high speeds, the world was still wide open to

animals. The few metropolises that choked out a species or two, or destroyed a

few herds of animals who couldn't migrate weren't really a problem on a global

scale. Even today I wouldn't say they are a global problem by themselves. We

have very few massive metropolitan areas. Some obvious examples in the U.S.

though would be New York City, which entirely blocks all of nature to a massive

area of land and water, most of the state of New Jersey, which looks like a

suburb from border to border, San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles metropolitan

area, San Diego. Some places like Chicago or Denver, although very large cities

don’t have continuous networks of massive urbanization, which makes them far

less destructive to larger species.

But if all the roads did was kill a few animals as they crossed, it would be more a problem for people than the species or nature in general. Worse is that with larger and more complex highways, continuous fencing, perpetual roadside urbanization, etc. These highways entirely cut off one part of an area from another.

California and its cities provide great examples of this growing problem with the common method of urban development. Cities and roads are designed as if they are isolated entities surrounded by the wild. But the truth is, it is the wild that is becoming isolated and surrounded. It's true for California and even highly urbanized areas like the San Francisco bay area that there is a lot of space for wildlife, however with its network of highways and cities, most of these areas are cut off from each other. It makes natural migration, particularly of larger animals, almost impossible.

California’s Central

Valley has a few good examples. There used to be an animal called the tule elk.

Now merely a roadside attraction of what once was, this species native only to

the Central Valley is virtually eliminated. It was hunted greatly, its

population severely reduced, but that’s not what ruined it. Numerous attempts

have been made for decades to re-introduce the tule elk to its native habitat.

Unfortunately that habitat is just not habitable anymore. Humans have designed

what is almost entirely open land to be worthless to big animals. Networks of

highways sending piercing death upon any animal that crosses, the tule elk isn't the only animal to be entirely driven away. Mountain lions also used to

inhabit the land, as well as the California golden bear, grey wolves, and

pronghorn antelope. Of these, only the mountain lions remain wild anywhere within

the state. In each of their cases, the elimination of habitat was a factor.

People have noted how

unpopulated and wild California looks from airplanes. This is partially true.

There are great expanses, the vast majority of the land is undeveloped and

uninhabited, but it is an empty state that has killed off nearly all its big

animals and those that remain on the fringe are in constant danger, because

even with all the space available, humans intentionally design to keep things

out and away. Large sized or herd animals need a great deal of space to obtain

their food and other necessities. There might be enough space in California for

thousands of elk, but isolated into pockets the elk can’t move, they can’t

flourish.

I think if cities and roads could be designed with "green corridors" throughout it could simultaneously improve the beauty of cities, reduce congestion, and afford animals a place to travel. In many places in the past people have made small scale efforts to this concept, like making a little tunnel under a street or fencing off highways and trying to make guides for animals like deer where they can cross without being hit by vehicles. But as far as I know nobody has tried a true corridor system. Certainly retroactive design would be more expensive and complicated than building new cities with corridors in mind, but targeted efforts at key spots might be feasible.

The cheapest and

easiest would be to address the highways that cut across states and nations.

They shouldn't be thousand mile long deadly barriers. Simultaneously, if the

highways could be addressed, that might cover the vast majority of problems for

wildlife. Now when I say cheapest and easiest, I still mean expensive and long

time consuming. In all circumstances doing it right the first time would be far

cheaper than “retrofitting” but some simple ideas would be to consider

particular wildlife areas and find ways of linking them together to form a

greater network. The links would have to be substantial, both singularly large

and numerous. One little bridge over a strip of land won’t exactly encourage

re-introduced tule elk in one part of the Central Valley to spread out and

flourish again.

The nature of the

“green corridors” would have to be carefully considered based on local

geography, the natural movement patterns of the fauna, and their ability to

manage a man-made corridor. For example I read it was discovered in trying to

make a path for a certain deer to migrate they found the deer wouldn't enter

dark tunnels. If this were the case for instance a corridor could be set up by

a river where a large highway bridge has already been built, or simply build

the highway up with an underpass. This highlights an already present fact that

highways don’t have any trouble going over rivers, bays, etc. the principle

would be the same going over land, each allowing nature a little thoroughfare

to mitigate complications. I have a few examples of such a concept.

Here is El Dorado and Center streets in south

Stockton, California. Both multi-lane central thoroughfares that run north-south

across the city. At this point they bridge over a former waterway, a rail line,

a couple rows of industrial facilities and some ground level streets. The over

pass is not too inconvenient. People walk, bike, and drive over it all day and

night. This could be a green corridor, the only difference is it would look

much more scenic, and would enable a fox and the rabbit it’s chasing to cross

the city without having to walk in front of someone’s car.

El Dorado Street again, this time mid-town at the Calaveras

River. The river runs through the city and merges with the delta on the

west end. In fact if you had a small boat or kayak you could travel

on this river, all the way to the west end of town, go south and follow the

channel back into town and end up only a few feet from the previous image as a

waterway stops just short of El Dorado in the previous image. Similarly a fish

could take the same trip, or an otter, or an errant dolphin as has happened on

occasion. This works because humans afford this little bit of nature to pass

through. It helps wildlife thrive to give them a corridor to avoid people and

cities.

This is an example of what I think is detrimental. It is the

generic highway design that crisscrosses this state and the nation. The image

is of west Berkeley, at the bay. (Aside: my brother says he hopped the fence and ran across this highway one night while he was visiting me). Highway 80 runs basically north-south across

the area. You can see at the lower end of the image aquatic park on the east

end of Highway 80, with undeveloped-open land and the San Francisco Bay on the

west end. Whether it has wild life on one side and the other, or city on one

side and wild life on the other, the highway is a dead zone. It cannot be

passed by land animals. There are fences, and other unnatural barriers, not to

mention many busy lanes of traffic. There is no break at any point along the

bay. What is west stays west, what is east stays east. If a duck wanted to move

some ducklings from the choppier bay side to the calmer lagoon, it’s not

happening. Might as well be separate continents. You might notice in the

picture there’s a bridge for humans to move over the highway, so they can move

from one wildlife spot to the next. But a beaver couldn’t do it. A coyote

couldn’t do it. A frog, not a chance in the world, that game of Frogger would

always end on level 1.

So to the eye it’s

pretty on both sides. Looks green. You would figure wildlife enjoys it, but really it’s

all cut off. Neither benefits from the other in ways it could. Sure some pollen

will make it over, birds and insects, but anything higher on the food chain

than a rat isn’t likely to be making it over. And this just goes on, from city

to city, around the entire San Francisco bay. Choking off a massive wildlife

area.

This image illustrates what I mean in a larger scale. You

can see I-5 cutting through the state. On the west you have hills and mountains

leading over to the Pacific Ocean. On the east you have open flat land,

marshes, fields, etc. With that I-5 cutting through though,

there might as well be Hadrian’s Wall between them. You might not believe it.

It is just one little line in a mass of nature.

Here is a street view image of the same area. You can

probably see that both sides of the highway are fenced off. It’s like that

virtually everywhere across the state. All the private property colliding into

main roads with nowhere for nature to get through. But even without the fences,

let’s watch how successfully a group of elk cross I-5. How would a pack of grey

wolves fare crossing in the night? Zip…zip…zip…cars just roaring through the

open land at a minimum of 80 mph. Imagine some poor bastard bear just wanting

to hit up the hills for some honey and he’s supposed to cross 4 lanes of top

speed interstate traffic.

Not happening. Ever.

That is why no large species can survive California. We've fenced it,

barricaded it, designed the state to keep things out or in, or in line, and it

worked.

This is the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. Looks

like a perfect wildlife refuge from this height. Lots of green and blue. Surely

if we dumped some tule elk in there they’d be ok. It’s literally their natural

habitat right? I mean, that’s where the tules grow best, right on the banks of

the mighty delta.

Here’s a close up of what virtually the entire Delta looks

like Massive mounds of cement, boulders, gravel

with dirt piled on top. Levees, everywhere levees. (Aside: I once set off fireworks with some friends right at this spot about 16 years ago). No trees are allowed on the

levees. No wildlife allowed on the levees. So you have no shade, no animals

cooling by the banks. The banks of the Delta are usually broken up blocks of cement next to dirt or cement roads,

poorly maintained, but certainly not wild. Slightly outside the borders from Stockton to Sacramento to Vallejo are houses, stores, and industrial factories

dumping waste into the water. Further out of the cities is the farmland. No place for

an animal to go rooting around. On the banks they’d be exterminated for potentially

weakening the levees. In the fields they’d be exterminated for eating or

otherwise hindering the crops. Could you imagine a tule elk, majestically

hiking its ass up the levee after walking across farmer Agosta’s tomato field,

carefully trying to steady its footing like a mountain goat while stepping

slowly down the levee’s big jagged wobbly boulder strewn bank to the water’s

edge to take a sip, oh but something has caught its attention, it needs to

escape. Certainly this being a massive wetland it could ford the narrow gap to

the other side and escape to safety. What’s that? The entire Delta has been

carved up into a cement and water highway for international ocean freight and

it’s 30 feet deep and fast moving water? Bye bye elk, you don’t fit here anymore.

Byyyeeeeee. That’s why they don’t find the bodies of people who fall in the

water and don’t know how to swim. It’s not a wetland. It’s not a marsh. It’s

channels and freight. Cement and crops.

I get that we need the farmland, that the Delta provides

excellent direct irrigation, that having navigable channels provide a great

boon to the Central Valley economy, and even the necessity for levees, at least

in some places. But it’s the absolutism that is destructive. There isn’t a more

open, wild refuge for the wildlife. The whole damn Delta is carved up and

commercialized. One simple action could be to move out the levees an acre or

two in some areas. You need the levee, fine, but why not put some land, and

some trees on the inside as well. So animals could walk up to a low bank,

animals could drink from the Delta without worrying about wobbly blocks of

busted up concrete and falling into a narrow 30 foot deep channel with no

visual protection while someone buzzes by at 20 knots with a skier in tow. Places

where a beaver or an otter could set up shop and not have to be euthanized for

the integrity of the levee. Restoring some of the wild to the delta could be

the most beneficial act of all, the Delta is a natural corridor linking the bay

area with the entire Central Valley and into the Sierras. Minimal effort could

be made to make California more beautiful, less cemented over, and better for

the entire ecosystem.

Speaking of which,

why is every major river coming out of the Sierras dammed up? We can’t just

have 1 river left free to flow? Don’t want to go off track, but a simple fact

is those dams are far more about the reservoirs they create than they are about

hydro-electric power. Their power is negligible. What the state really enjoys

is being able to control how much water flows across the state. They’ve been

systematically killing the Delta for years cutting short the river’s flows,

meanwhile continuing to raise the amount of should-be Delta and farmland water sent down south to L.A. where more and more people build cities with big green yards

and swimming pools green parks, in a desert, sucking up the state’s water for frivolous

shit and killing another habitat, as they have in the past. Knocking out

ecosystems to have pretty grass where it doesn’t rain. (if you don’t know what

I’m bitching about, there’s an epically massive aqueduct system that has been

funneling water to southern California for decades, after SoCal exhausted

another ecosystem at the south end of the valley. Without this water, L.A. and all

its surrounding cities couldn’t exist the way they do, wasting water and acting

like they aren’t in a low rainfall area, meanwhile the Delta and farmers in the

north are left with the scraps. But this is a bit off topic, although in the

bigger sense indicative of the larger mentality of California’s people and

government believing they can control and regulate every aspect of nature).

Creating “wildlife crossings” to recover from “habitat

fragmentation” (thanks Wikipedia) are not new ideas. However they have been

sparsely applied and often derided, particularly in the U.S. Here are some

examples of an underpass and some overpasses designed specifically to enable

animal passage.

With enough in place in the right areas wildlife crossings

through highways, and the greater effort of linking those to areas of actual

wilderness and not simply fenced off farmland, the majority of California’s

wilderness could be once again traverseable. The largest effort I've read of is

the European Green Belt, which has been an effort for decades to preserve a

natural green belt that formed due to the political separation of Europe and

the “Iron Curtain”.

It is a common occurrence that where there are political borders

and military boundaries, wildlife seems to thrive. This can be seen even

locally along the California border with Mexico where the majority of the land

on either side has a large wild area with cities dispersed. Another large one

that comes to mind is the DMZ between North Korea and South Korea. As almost

all people are forbidden in the central area of the DMZ which is about 2.5

miles wide and 160 miles long, it has become an extremely effective nature

preserve.

I have yet to mention the ocean and beaches but I am more acutely aware of the damage human habitation has caused this habitat than most others. My whole life I have been fascinated with the shore and the ocean. I have never lived more than 100 miles from the ocean in my life and about 1/3 of my life I’ve lived in a city on a bay or directly ocean side. I have swam with sharks and dolphins and various rays, I have crawled into the crevices, caves, and tide pools from Florida to California, Australia to Japan, and several islands of the Pacific, states, territories, and foreign lands.

The most profound and striking example I can give was while

stationed on a ship in Coronado California in the Navy. The San Diego bay is a

relatively large bay. It is also a very populated area. Coronado forms the main

barrier to the ocean, forming the bay as the ocean crashes on its western shore

and ships pass in and out along the northern end of North Island. A typical day

in the Navy we were getting shooting qualifications at the base’s gun range.

The gun range was designed so everyone would shoot west, towards the ocean.

There was a massive earthen barrier to catch all the fired bullets, but angling

it towards the ocean was a secondary precaution. There was about 600 feet from

the earthen barrier to the ocean (Google verified). There was vegetation, some grass and bushes.

The area was already relatively secluded; being on the north-west end of the

Navy base with a big airfield surrounding it there weren't a lot of humans who

were allowed to be anywhere near there (and fewer still who had any reason to

be). But because shooting was occurring and people liked to run up and down the

beach, I was assigned to stand on the beach and tell people not to run further

than the giant sign that read “Shooting range, do not blah blah blah”.

So with this odd Navy watch, I’m out by myself on an empty

beach for an hour staring at birds. No hustle and bustle, I am afforded the

chance to soak in the beauty of my position. I begin looking around and I

realized I was looking at the most wild beach I’d ever seen in California. I've been to the shores of Guam and Saipan where crabs and mudskippers run around

freely, trees meet shoreline, with your bare hands you can just scoop up various

fish, turtles, or eels if that’s your folly. I've also swam with dolphins in

estuaries surrounded by forest in Florida, swam into a creek from the lagoon

and experienced the immediate change from warm salty water to cold fresh water.

Little things like that here and there. But most of California shoreline is

either a vertical cliff or people as far as the eye can see walking on barren

sand, a shell a rarity. Perhaps a bird or two. Only in the rarest places with

close to shore large rocks would one see a sea lion or a seal come close.

This was probably the

most beautiful and diverse scene of wildlife I have ever experienced. It was

absurd how many different species I was looking at standing on this beach.

There were nesting shore birds, there were gulls, there were pelicans diving

into the ocean for fish, there was a pod of dolphins about 100 feet off the

shore feeding on the same school the birds were. Sea lions were swimming back

and forth, some on the beach, others out by the buoys that guided ships into

the bay. I saw a pack of jack rabbits run past. I’d seen jack rabbits all over

North Island, but never in a pack. I don’t even know if that’s normal. It was

like one of those nature posters people get with an impossible number of wild

animals all just hanging out in one area.

I thought about this fantastic

sight and it dawned on me, this was a rare piece of ocean shoreline among few near

San Diego, for miles in each direction that isn't completely covered in people,

houses, or commercial operations. A tiny bit of wild beach tucked away and

protected from humans, because of a gun range at a naval station. I had seen

other little fringe pockets like this. Over by my ship when the mooring lines

are out sea birds would sleep on the lines, the tucked away piers forbidden

from the general public also provided quiet places for sea lions which I would

see swim by sometimes, but they never had a safe place to come ashore. Even in

the protected areas to the north and south, and a couple in the bay, you’re not

likely to have such limitation on the foot traffic. You can call a place a

preserve all you want, but if hundreds of tourists a day are walking all over

the place, the wildlife will remain sketchy.

Up by San Francisco it might be even worse.

Although San Francisco bay is huge, there are few places in the bay safe for

wildlife. There is almost no area along the city of San Francisco that provides

safe harbor for wildlife. Although, interestingly there is Pier 39 where there

is a literal safe harbor that has been left to the sea lions.

Wedged inside one of

the largest tourist areas of one of the most tourist destined cities hundreds

of sea lions find refuge on a few planks of wood. Such may be the simplicity in

securing safe places for wildlife to reside. I have read of several other successes,

one was of an effort to

create a corridor for wolves through a golf course in Alberta Canada. The

report states that originally the wolves would go around the course, and that

elk would traverse the course. When they built the corridor, the wolves quickly

adapted and began hunting the elk, which then caused the elk to more evenly

disperse. To quote the report: “ Our results corroborate other studies suggesting that wolves and elk

quickly adapt to landscape changes and that corridor restoration can improve

habitat quality and reduce habitat fragmentation.”

This brings me to my

final suggestion, one that I actually originated. I came up with the idea while

taking a human geography course. The idea was a sort of meshing of typical

human development. It satisfied a desire I also had in designing civilization in

a way that a person could presumably walk from one end of a city to the other

without ever stepping on cement. This same ideal could be applied statewide. If

such a design could be made, then wildlife could do the same. This city design particularly

works for a metropolis area where there is no way a corridor could be set up,

as civilization dominates the entire area.

The idea is based on a standard model of human urban development.

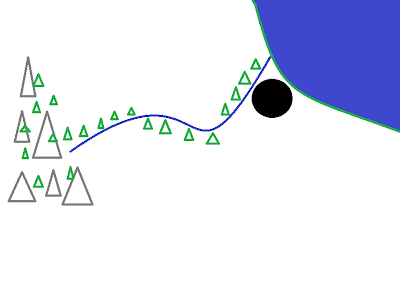

Bear with me I spun this out of Microsoft paint in about half an hour.

Stage 1 shows a mountainous area, some forested areas, and a

river leading to a body of water. Everything wild and natural (Imagine the green triangles represent forested area, the gray triangles mountains, and the blue is water, a river and a lake or bay).

Stage 3 shows a second development. Still plenty of room for

all, but soon those from development one and development two will create a far

more complex network to trade with each other.

Stage 4 shows a complicated network of roads, towns, and

cities. As wildlife can’t cross the black, habitat fragmentation is beginning.

However the major land areas are still wide open.

Stage 5 shows the progress of urbanization and

industrialization. Now cities are greatly influencing far beyond their borders

with rural land (in orange) dedicated to feeding and supplying the cities

locally and abroad. As cities expand their borders they combine and form large gapless

urban areas.

Stage 6 is the metropolis. Now almost all the cities border

each other. Former rural land has been taken up by cities, and new farm land

had to be carved out at greater distances. At this point wildlife is entirely isolated

in various regions, the mountains are blocked from the flat land, the flat land

is blocked from the body of water. The river, the only thing remotely wild

running through the city is being sent underground at places, and is being

managed as a burden, not a place of refuge or nature.

The benefit to this concept, whether proactively in new development,

or retroactively, is that if it is done right, it would be a minimal hindrance while affording massive metropolis areas

to continue to expand, or cities to become even more networked and populous,

while simultaneously keeping nature linked with itself. It is a concept of

minimal effort to preserve a fraction of nature while cities expand and

urbanization takes up more and more space.

Retroactive measures in this regard will probably be quite

expensive and very time consuming. However this is a plan for human development

to improve in a way that mutually benefits humans and nature, it isn't a

quick fix. It is more a last ditch appeal for conscious urban design with

regard to the well-being of all life forms.

Looking at some cities I noticed San Francisco is a prime

candidate for such a conceptual design.

In this crude work I have outlined in green the larger parks

within San Francisco. In blue I have shown where these parks might be

connected, which if done could create a green belt throughout the city. Of

course as this might be a long process it isn't thought that houses would just

be torn down, and all areas returned to the wild. This would have to be an

intelligent, well planned, well-funded, long term design. And even after parks

are connected, that certainly wouldn't be the final step, the areas would have

to eventually make paths, re-route roads, etc. so that foot traffic and human development

is removed from the key areas and choke points, this way to encourage wildlife

travel.

What’s brilliant

about San Francisco is that it already has so many large and expansive wild and

tamed park land that very minor efforts could yield massive results. For

example connecting Golden Gate Park, to the Cliff House area, to the Presidio

wouldn’t take much at all, there are already mostly green paths connecting them

in the first place, the only thing blocking them is some roads. A few bridges

and you’d have the biggest inner city connected park system in the world.

Another one is the Mt. Sutro/Twin Peaks area which is separated from Golden

Gate Park by only 2 blocks. It would be expensive and time consuming, but

not unfeasible to buy up that land in between and link the two. All

over the city relatively little areas could connect relatively large areas and

provide a vast network for wildlife, or just people like me who want to walk

from one end to another without cars or street signs in the way. What I noticed

really provided some opportunity were the highways. On either side of them is

already a green belt. If this were expanded, re-enforced and linked to the

other parks it could be an instant long corridor across a large portion of the

city.

Most other cities weren't designed with so many parks so linking anything would be difficult, but not impossible. Stockton as I showed earlier has rivers and waterways that span it leading into the Delta on the west side. While it’s unlikely Stockton’s parks could be connected, and it has almost no wild life areas within the city limits, the rivers and Delta could be used as focal points for expansion. Rather than having the Calaveras River for example running as an ugly straight line in a grey bowl of rocks across the city, areas of it could be expanded, putting the levees further out, enabling a green path possibly a more riparian environment that would be simultaneously beautiful and better protection against flooding. It would benefit the environment, promote cleaner water, strengthen the fish populations, etc.

One area in particular in the San Francisco Bay I think would make a good link is the mountain ranges connecting to the bay. They are unfortunately entirely separated by thick population with an unending series of cities from San Francisco all the way down to San Jose and all the way up the east end up to Rodeo just south of Vallejo. In these mountains there are some of the few remaining mountain lions, which have been cut off from each other with one population in the western mountains and another in the eastern mountains. This fragmentation could eventually prove destructive for them in trying to find viable mates. However the reconnecting of the two ranges and connecting to the bay could be considered two separate projects with different end goals. One of the more viable options I found in the east bay was surprisingly Oakland. There are lengthy parks coming out of the mountains that almost connect with Lake Merritt. With Lake Merritt there is already an establish path to the bay that could be expanded for more wildlife. Oakland could in this way, by opening space and planting trees along the route, restore some of its oak land from which it was originally named.

Retroactive designs would certainly be more expensive than

designs built into a city as it progresses. This is partially why I believe

such efforts should begin now, while there is still wilderness, rather than

after the fact trying to bring it back. As was seen with the tule elk, this isn't necessarily as simple as raising some animals and putting them back out

where they used to be. When we fundamentally alter an environment, it’s a

massive operation trying to change it back. It was the built-in design that I

originally conceived of and have been trying to hand to people to look at for

years now.

I couldn't find a previous one, so I just drew this and

scanned it. Imagine this as a portion of a city. Most cities are basically laid

out on a grid with property blocks intersected by streets. This is the same

idea, but it also weaves in corridors of open space (shaded green). This concept can be minimized

to only a few corridors, it could be expanded to having large corridors, have

big open parks or largely industrial areas with nature only on the fringe. A

creek or river could be the central path with branching corridors. The premise

is the same. Rather than making cities as big blocky dead zones, they could

contour to nature, keep the grove of trees, don’t bury the river, let the city

go an extra square mile at the benefit of being absolutely gorgeous, and not

just a cement jungle.

Whenever I come up

with some big idea and try to tell people about it, people around me often

express a measure of skepticism that anyone would ever take it seriously or

consider the idea. While a constitution based on a new political theory might

be reaching for the sky, this is just an idea for a neighborhood. There are

guys like Spanos or Grupe around Stockton spitting out completely new

neighborhoods every few years. There’s a long standing political hot button issue

in Stockton, many people don’t want any development north of 8 Mile Road, on

the other hand Spanos likes building, and all the well-to-do in Stockton hate

Stockton. Nobody with money wants to get anywhere near downtown. The only

option is to keep building away. Now if my ideas were incorporated, perhaps it wouldn't be a political problem. If you could show that a green belt would be

maintained and respected, one that passes through the neighborhood, rather than

progressively claiming wherever you stop developing, that’s where the “green

belt” begins (as we know in reality this “green belt” is just a place holder

for future development) the design actually protects nature, rather than

threatening it.

Everywhere

on Earth I go I see people design neighborhoods and cities as monuments to the death

of nature. Architects have spent thousands of years coming up with all kinds of

radical designs. But then when you look at how civilization is arranged, it’s

all the same. While looking up information for this blog I found a website

proposing a long list of ideas of how to improve urban design to help the

environment, no mention of actually giving nature a designated place. Japan

provides a good example (although not intentionally) of urban design that

preserves much of the environment. As Japanese cities are almost all built up,

and very dense, it leaves the vast majority of the country uninhabited. Japan’s

cities don’t take up much space but they still have roads and trains all over

the place cutting off animals, and they have made many mistakes Californians

have, such as cementing and damming up all their rivers. But even if you

followed the Japanese model elsewhere, and stepped it up by steering clear of ruining the

habitats of giant magical salamander monsters, you're essentially trying to force people to live a certain way most people don't like, a rather plugged up and uncomfortable way, trading human comfort for the benefits of wildlife, yet still choking them out with your Tokyos and other metropolitan behemoths that entirely block nature from one end to another.

This brings up one final benefit of this kind of city design. In the past people have made efforts to recreate the pastoral or rural model while enabling a multitude of people to live relatively closely. There were the "green cities" entirely pre-fabricated towns that greatly incorporated the rural that were initially very popular in the United States, but fell by the way side during the depression, never to be recreated. Although those cities today are still very popular to live in. These cities, while still using the old barriers, at least acknowledged for many people a desire to live closer to nature. Post World War 2 suburbs became very popular in the U.S. If you look at a suburban neighborhood you will see the intentional pastoral design, as all the houses are built away from the street with every plot of land having a big green yard and a tree or two. Entirely a marketing gimmick it gave the illusion of a pastoral environment, without there being any actual possibility of a deer wandering through your meadow of front yards (unless your neighborhood borders an actual wildlife area). What my idea does that no one has ever done before is make it real. It won't be the illusion of wildlife, it won't be a quasi-green neighborhood fenced away and surrounded by highways, it will be actual nature and humanity side by side, in a way that doesn't require one to kill the other.

I believe there is something better and more natural to humanity in being able to create some natural gaps in urban landscapes. As I mentioned at the beginning of this proposal, humans naturally spread themselves out across the world. We can see it in the US and California as well. When the Spanish first established missions in California they spread across the state, even when the population was mere thousands you had cities from Monterey to San Diego. We like space. We like knowing who our neighbors are. I've heard people work better in smaller groups than in massive offices. Smaller class sizes, more familiar local officials, everything about our minds our desires, our nature is an appreciation of bringing things closer to us. The human becomes lost in the megalopolis. When people live in massive cities, they don't even bother to get to know who lives in the apartment next to them. When people live in small towns, everyone gets to know everyone else. But of course some people do want to get lost. This design doesn't negate that. There's perfectly valid and great reasons to have some massive downtown areas to cities. But for those looking to raise a family, or get a little more quiet, putting some space between could be a vast improvement to quality of life, with the fringe benefit of not destroying an ecosystem.

-Nearly all images stolen. Overhead and Street View images from Google. All other images from Wikipedia, except for that Salamander photo.

-Microsoft Paint images original works, all the rights I ignored for Google and Wikipedia reserved. Scan of hand drawn urban design original work, all rights reserved. If you steal it anyway please send me some of the billions you make from the idea.

No comments:

Post a Comment